During the 2019 New Mexico Legislative Session, the Southwest Women’s Law Center (“SWLC”) and Forward Together/Strong Families (“FT/SFNM”) partnered on a legislative advocacy project resulting from the failure to pass House Bill (HB) 51 which would have repealed New Mexico’s dormant abortion ban.

In talking with legislators who were either Native American or represented significant Native American constituencies, many expressed the belief that Native Americans, as a monolithic group, are against abortion. The SWLC and FT/SFNM believe this stereotype caused some Democratic senators to vote against HB 51 (a few of whom had initially pledged to vote for HB51 and then recanted on that pledge), causing it to fail.

After the close of the 2019 legislative session, the SWLC recognized the need to address these stereotypes, and partnered with FT/SFNM to conduct a survey of Native American experiences and attitudes towards abortion care and reproductive healthcare in general. In 2017, FT/SFNM conducted a survey of rural New Mexicans’ attitudes towards reproductive health, which provided preliminary evidence that Native Americans who lived in rural New Mexico had progressive views in this policy area. The SWLC also discovered that there had never been a survey directed only to New Mexico’s Native American population. This survey was meant to be a more focused look at these attitudes.

The SWLC and FT/SFNM contracted with opinion research firm Latino Decisions, and in March and April of 2020, they conducted a mixed mode (phone and internet) survey of over 300 Native American adults in New Mexico. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest sample of Native Americans in New Mexico ever collected for the purpose of understanding experiences of Native Americans and attitudes toward reproductive health policy.

The survey sought to illuminate the diversity of opinions on a range of reproductive health topics within the Native American population of New Mexico and to discover any trends. The SWLC and FT/SFNM plan to use this data to identify whether there are needs within Native populations that we should be addressing, what approaches would be most beneficial, and inform legislators about the diversity of opinion among their Native American constituents.

Methodology

Latino Decisions conducted the survey Attitudes Toward Reproductive Health Policy Among Native Americans between March 24, 2020 and April 7, 2020, completing 302 interviews of Native American adults in New Mexico. Of the 302 completed interviews, 158 were conducted over the phone (cell-phone/landline) and 144 were web-based.

The data collection effort was aimed at ensuring the sample was reflective of the state’s Native American population. The survey included several demographic factors to compare the outcome of these measures with data from the US Census. The results were weighted to known population characteristics using the Current Population Survey from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. The nominal margin‐of‐error for the poll is 5.6%.

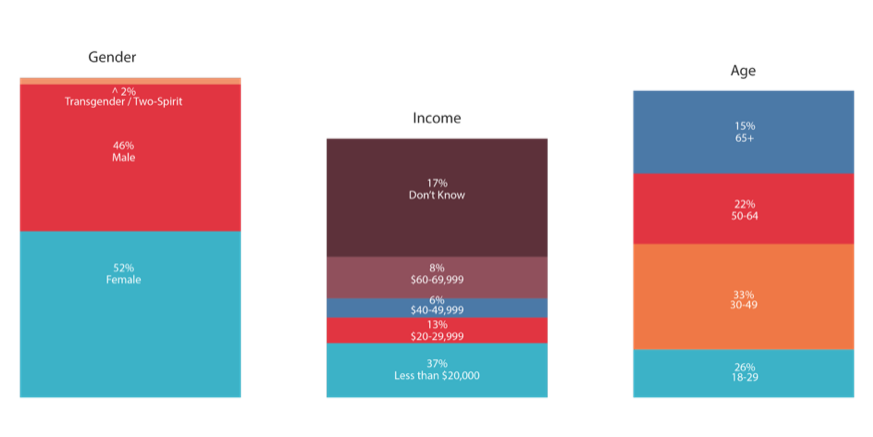

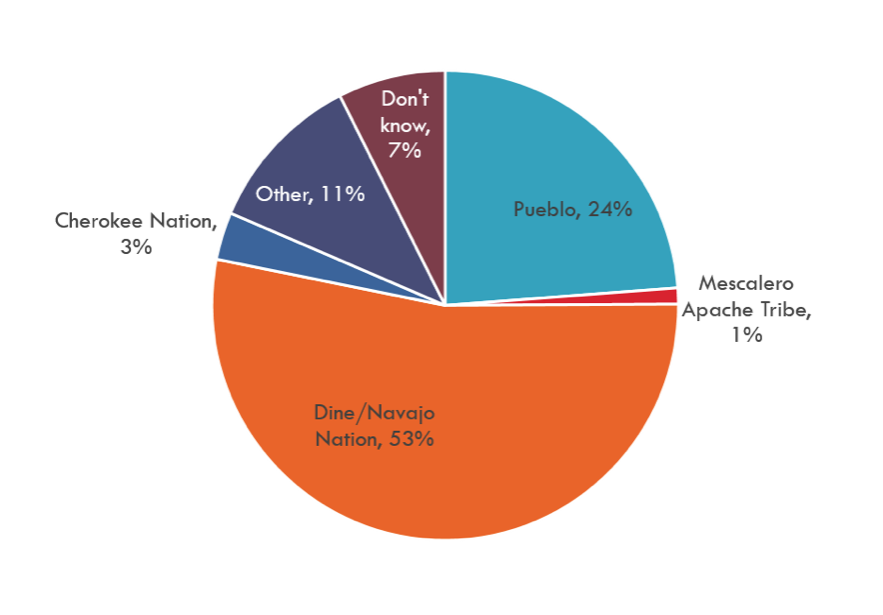

We have included several figures from the demographic content of the survey to provide the ability to assess the sample’s demographic profile.

Demographics

Slightly over half of respondents are affiliated with the Navajo Nation. The Navajo Nation is the largest Indian tribe in New Mexico, and one of the largest in the continental United States. Just about a quarter of respondents are Pueblo. Pueblo respondents came from 18 of the 19 Pueblos, with generally 1-2% of the sample from each one, and 6% from Zuni. The only Pueblo not represented is the Pueblo of Zia. Additionally, 3% are Cherokee Nation-affiliated, 1% are Mescalero Apache, 11% marked “Other,” and 7% didn’t know. This is roughly proportional to the population of each tribe in New Mexico. The majority of respondents are enrolled tribal members, at 77%; eighteen percent were not enrolled and 5% didn’t know. This is a higher rate of enrolled members than most of the New Mexico surveys conducted by Latino Decisions in the past.

Respondents were 52% female, 46% male, and 2% transgender or two-spirit. The age of respondents was varied, although all respondents were 18 years or older. Nearly half of respondents live on reservation or tribal lands, while 37% live off tribal lands and 14% split time across both areas.

Perceptions Regarding Access to Reproductive Health

When asked, “do you think Native Americans in your community have access to reproductive healthcare?”, 65% of respondents said yes, 22% said no, and 13% said that they didn’t know. Respondents living in rural areas or on tribal lands were the most likely to say they had access, at 67%, while respondents living off tribal land or in urban areas were much more likely to answer in the negative (42% and 35%, respectively). From this data, it seems that reproductive healthcare is less attainable for Native Americans living in cities, away from tribal lands. This might be explained by the data that 81% of respondents receiving healthcare from IHS or Tribal 638 clinics reported that they were able to access the reproductive health services they want and need. Alternately, it could be related to a greater awareness of the spectrum of reproductive healthcare by respondents in urban areas, and an attending perception that Native Americans in these urban areas are unable to access such care.

These responses on reproductive healthcare access must be contrasted with those answering whether respondents’ healthcare provider offered abortion services: only 29% of respondents said “yes.” The group that was most likely to say that Native Americans in their community had access to reproductive healthcare was the least likely to say that a clinic in their community provides abortions: Native Americans living on reservations and tribal lands (67% v. 10%). This discrepancy may be explained by the exceptionalism afforded to abortion care, specifically the preconception that it is not “normal” reproductive healthcare. The fact that abortion access is so limited on reservations and tribal lands can be attributed, at least in part, to the Hyde Amendment.

The Hyde Amendment prohibits the use of federal funds on abortion, except in a few cases (rape, incest, threat to the woman’s life), and this limitation affects Indian Health Service (“IHS”) clinics because they rely on federal funding. Surprisingly, active military respondents who are Native American were the most likely to say that a clinic in their community provides abortions (55%), despite the fact that the military’s TRICARE program is also subject to the Hyde Amendment. Urban respondents and those living off tribal land were the second most likely (44% each) to say that a clinic in their community provides abortion.

Thirty-seven percent of respondents reported that they were currently receiving reproductive healthcare from IHS, and a further 4% from Tribal 638 clinics. Of those who don’t receive healthcare at IHS, 29% said that they were uncomfortable receiving their care at IHS clinics, 17% said it was because of the quality of care they receive, and 13% cited difficulty getting an appointment. The lowest percentage (5%) marked that they don’t go to IHS because these clinics don’t provide the reproductive healthcare that they want or need.

The majority of people surveyed (89%) agreed that Native American women and families deserve to make their own healthcare decisions without government interference.

Attitudes Regarding Abortion and Reproductive Health Policy in New Mexico

When asked whether they would support or oppose a law that would make it a criminal offense for doctors to perform abortions, 45% of respondents said they would oppose, 25% said they would support, and 27% said they didn’t have a strong opinion either way. Broken down by political affiliation, Republican respondents were the most likely (38%) to say they would support making abortion a criminal offense. Only 22% of Independent respondents and 23% of Democrat respondents said they would support such a law. While men and women opposed such a law at approximately the same rate (45% and 44%), men were more likely to support the law (31% v. 21%) and women were more likely to say that they didn’t have a strong opinion either way (32% v. 21%). Active military respondents were by far the most likely to support abortion criminalization at 55%, while veteran respondents were the least likely to support, at 16%. In general, Native Americans in New Mexico are against making the provision of abortion care a criminal offense, and more respondents said they didn’t have a strong opinion than those who would support criminalization. Because the question did not specify that this would criminalize safe abortions, it is unclear whether some respondents who were supportive or ambivalent about criminalization were thinking of unlicensed or harmful doctors performing unsafe abortions.

Many respondents (59%) agreed that, if someone they care about has made the decision to have an abortion, they want them to have support—only 20% disagreed. When asked if they can hold their own moral views about abortion and still trust a woman and her family to make this decision for themselves, 72% of respondents said yes. This shines a light on the complexity that is often missing from national debates around abortion: people hold nuanced views, and even those who are not in favor of abortion recognize the humanity and need for support of people who decide to have an abortion.

Personal Experiences with Reproductive Health Challenges in New Mexico

Respondents were asked about their own experiences with abortion, miscarriage, infertility and sexual violence, as well as how those experiences shaped their views.

Around one-third of respondents (35%) said they have a friend or family member who has had an abortion, and 20% said they or their partner had accessed abortion care. This is consistent with national rates of abortion frequency. Fourteen percent of respondents or their partner had experienced infertility or trouble getting pregnant, and 21% had experienced a miscarriage or stillbirth. Nationally, 10-20% of known pregnancies end in miscarriage and about 1% in stillbirths, putting these survey responses on the high end of prevalence.

An equal portion of respondents (43%) said that their own experiences around reproductive healthcare “has made me realize we need more access to reproductive health[care] in New Mexico” and “has not had any impact on my views.” Only 10% of respondents said their experiences “made me realize we need less access to reproductive health[care] in New Mexico.”

Respondents who have personal experience with abortion listed who they turned to for emotional support: 45% turned to a family member, 41% turned to friends, 27% to their partner or spouse, 17% to a medical provider, 12% to internet support forums, and 5% to a faith leader (respondents were allowed to choose more than one). A quarter of respondents say that they didn’t seek or need support, while 11% said that they didn’t have the support they needed. This question was only asked of a small number of respondents, and so responses should be viewed as anecdotal, not statistically significant.

Twenty-two percent of respondents had been the victim of sexual assault or violence at some point in their life. In the US, 1 in 3 women and 1 in 4 men experienced sexual violence involving physical contact during their lifetimes, and this data is consistent with those national rates. It bears noting that sexual violence is underreported, and the real incidence of sexual violence is higher than the numbers show.

Experience with Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC)

Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC) includes intrauterine devices (IUDs) and subdermal implants, which provide low-level doses of hormones that inhibit fertilization of the egg. LARC is one of the most effective forms of birth control, but also one of the most expensive in terms of up-front costs. In the US, LARC can cost up to $1,000 out-of-pocket, although it is starting to be covered by more insurance plans. Additionally, healthcare providers must be trained in LARC insertion and removal, which has meant that not every office prescribing birth control has the experience or capacity to offer LARC.

In this survey, 57% of respondents said their healthcare provider offered LARC, 25% said they did not, and the remainder didn’t know. When this data was broken down by healthcare provider, 69% of respondents who received their healthcare from Indian Health Service (IHS) said that their provider offered LARC, compared with 59% from Tribal 638 clinics, and 50% from other providers. Respondents living off reservation were more likely to say that their healthcare provider offered LARC than respondents living on a reservation (74% v. 64%). Additionally, Pueblo respondents reported more access to LARC, at 67%, than Navajo respondents, at 56%. This is likely because of the relative locations of Pueblos and the Navajo Nation. The Navajo Nation, which covers a tremendous amount of land, is located in the northwestern region of New Mexico, which is more rural and frontier, whereas Pueblos are generally located on the Rio Grande corridor, near larger population centers, except for Zuni, Acoma, and Laguna Pueblos.

Fifty-eight percent of female respondents have never used LARC, while 14% had used it in the past, but are not currently using it, and only 8% are currently using LARC.

Of the respondents who had been prescribed LARC, but hadn’t used it, 67% said that this decision was because they had heard LARC can lead to problems with pregnancy after removal of the device, 27% said they preferred other options, while 18% said they heard it was a painful procedure and 15% said they felt pressure not to take it. This is once again a small subset of the total respondents, and so the numbers are not statistically significant, but they do indicate that there is misinformation about LARC’s long-term effects.

Key Take-Aways

Native Americans in New Mexico have varied attitudes and experiences around reproductive health; as suspected, they are not a monolithic group. The data shows how different affiliations and demographics relate to disparate viewpoints within the Native American population of New Mexico, and that even these other factors don’t fully account for an individual’s beliefs.

Native American constituents are not generally opposed to abortion. They are more likely to oppose the criminalization of abortion than support it.. Native Americans overwhelmingly agree that their women and families deserve to make their own healthcare decisions, free from government interference.

There is room for improvement in Native American access to abortion and other reproductive healthcare.

Recommendations

The SWLC and FT/SFNM should share these findings to indigenous-lead organizations, Native American advocates, and those interested in serving Native populations, and partner on next-steps. While the data is a useful starting point, it is important to collaborate and support Native American advocates in order to make sure that plans are responsive to the needs and sensitivities of this demographic, and that the organizations remain accountable to the people they are trying to serve.

Misinformation about LARC is common, and the data shows a concern with LARC’s impact on subsequent pregnancies after removal of the IUD. In addressing this information, it will be important to consider who is delivering the message and whether they are deemed trustworthy, especially because of the long history of medical abuse of Native American women and families in the US.

In addressing LARC uptake and contraceptive use, the SWLC, and other partners should pursue strategies that build trust between Native American patients and healthcare providers. This will include making it easier for patients to get whichever kind of birth control they choose, whether it’s LARC or not, and facilitating both easy insertion and removal so that patients don’t feel compelled to keep LARC. Part of this effort will be continued work for parity in provider reimbursement rates for insertion and removal of LARC.

The Hyde Amendment continues to pose an obstacle for patients who wish to receive a full range of reproductive health services, including abortion, at IHS. There is a broad-based movement to repeal this amendment, and to the extent possible, the SWLC and FT/SFNM should continue and support and participate in the repeal of the Hyde Amendment. In the interim, IHS and 638 clinics are permitted under the Hyde Amendment to perform abortion care for individuals who fall under the exceptions built into the Amendment. Upon information and belief, still both IHS and 638 clinics are not providing this reproductive health service, or it is very limited. Follow up conversations should occur with the IHS about this. Pending repeal of the Amendment in total, the SWLC should continue working with reproductive health and justice partners to ensure that IHS and 638 clinics are providing every reproductive health service as allowed by law to Native individuals living in New Mexico.

Last, the partnership of organizations serving Native Americans in New Mexico should investigate why healthcare access in urban areas seems to be worse for Native Americans than on reservations or tribal lands. There may be hidden barriers to access that need to be addressed.

***

References:

1 This summary was authored by Kearney Coghlan, Harvard Law School, Class of 2022, Student and SWLC Summer Law Clerk, with the supervision of Terrelene Massey, Esq., (Navajo), Executive Director, and Wendy Basgall, Esq., Staff Attorney.

2 Recognition of Partners on the survey Attitudes Toward Reproductive Health Policy Among Native Americans: Survey Development and Research: Southwest Women’s Law Center, Forward Together/Strong Families New Mexico, and Latino Decisions. Part 1 of this research on rural New Mexico included the work of Bold Futures. Contributing Organizations: Indigenous Lifeways and Tewa Women United. Compilation and Analysis: Latino Decisions. Additional national data analysis provided by Forward Together/Strong Families New Mexico.

5 https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/factsheet/fb_induced_abortion.pdf

6 https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pregnancy-loss-miscarriage/symptoms-causes/syc-20354298; https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/stillbirth/data.html

7 https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/sexualviolence/fastfact.html

8 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3662967/

9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29544988/

***

In collaboration with: